Whole Transcriptome Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to whole transcriptome profiling, a powerful approach for analyzing the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample.

Whole Transcriptome Profiling: A Comprehensive Guide to Methods, Applications, and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive introduction to whole transcriptome profiling, a powerful approach for analyzing the complete set of RNA transcripts in a biological sample. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers foundational concepts, key methodological approaches including RNA-Seq and single-cell analysis, and their diverse applications in drug discovery, biomarker identification, and precision medicine. The content also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for robust experimental design and explores the comparative advantages of transcriptomic data over other omics layers, such as proteomics, for validating biological function and guiding clinical decision-making.

Decoding the Transcriptome: Foundations and Discovery Power

Whole transcriptome profiling represents a comprehensive approach to understanding gene expression by capturing and quantifying the entire RNA content within a biological sample. Unlike targeted methods that focus only on specific RNA types, this technique provides a complete landscape of the transcriptome, encompassing all coding messenger RNAs (mRNAs) and a diverse array of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) [1] [2]. Every human cell arises from the same genetic information, yet only a fraction of genes is expressed in any given cell at any given time. This carefully controlled pattern of gene expression differentiates cell types—such as liver cells from muscle cells—and distinguishes healthy from diseased states [1]. Consequently, understanding these expression patterns can reveal molecular pathways underlying disease susceptibility, drug response, and fundamental biological processes.

The transcriptome consists of multiple RNA classes: protein-coding mRNAs, which serve as blueprints for protein synthesis; and various non-coding RNAs, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and microRNAs (miRNAs) that perform crucial regulatory functions [2] [3]. Technological advances, particularly high-throughput DNA sequencing platforms, have provided powerful methods for both mapping and quantifying these complete transcriptomes. RNA-Sequencing (RNA-Seq) has emerged as an innovative approach that offers significant qualitative and quantitative improvements over previous methods like microarrays, enabling detection of genes with low expression, sense and antisense transcripts, RNA edits, and novel isoforms—all at base-pair resolution [1]. This comprehensive profiling bridges the gap between genomics and phenotype, providing a powerful tool germane to precision medicine and therapeutic development.

Technological Basis of Whole Transcriptome Analysis

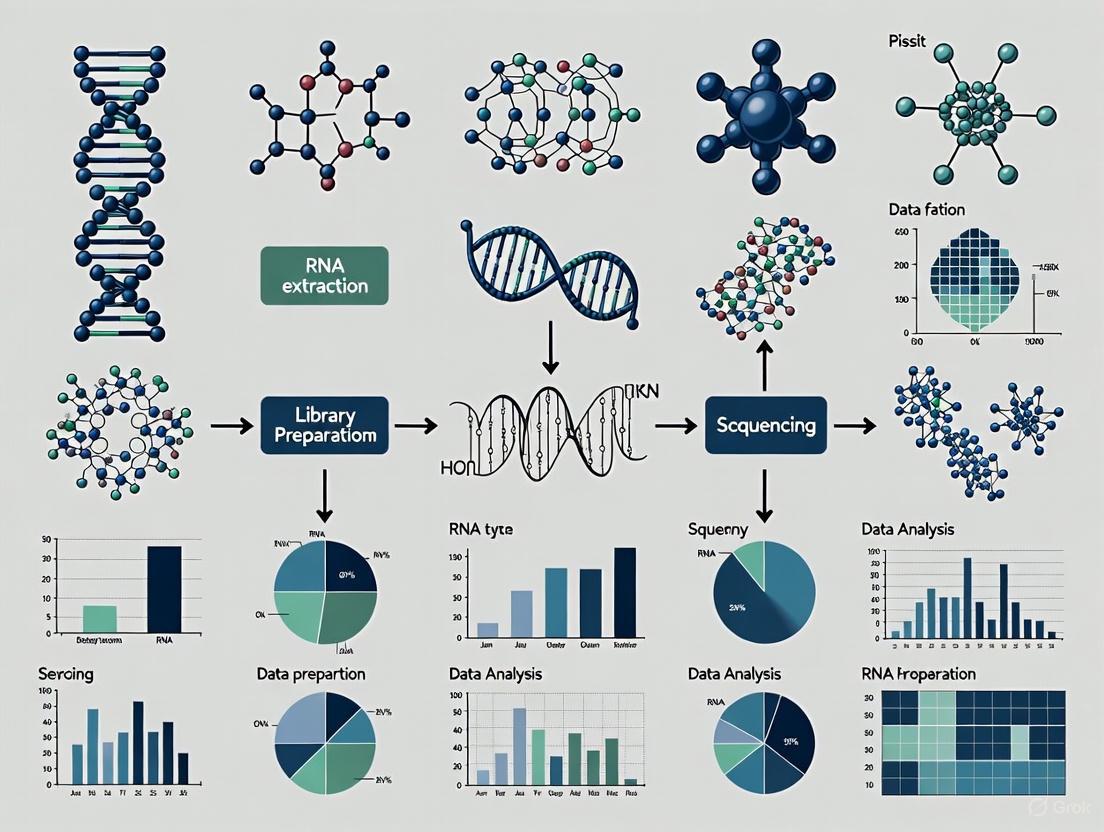

Core Methodology and Workflow

The fundamental workflow of whole transcriptome sequencing begins with RNA isolation from biological samples, followed by removal of highly abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which can account for as much as 98% of the total RNA content [2]. This rRNA depletion step is crucial for optimizing sequencing reads covering RNAs of actual interest. Unlike mRNA sequencing that uses poly-A selection to target only polyadenylated transcripts, whole transcriptome sequencing prepares libraries from the entire RNA population after ribosomal depletion [4] [2]. The remaining RNA undergoes reverse transcription into complementary DNA (cDNA), which is fragmented, adapter-ligated, and sequenced using high-throughput platforms such as Illumina [1] [2].

Following sequencing, millions of short reads are computationally mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome, revealing a comprehensive transcriptional map [1]. This alignment process is particularly challenging for reads spanning splice junctions and those that may be assigned to multiple genomic regions. Advanced bioinformatics tools use gene annotation to achieve proper placement of spliced reads and handle ambiguous mappings [1]. Overlapping reads mapped to particular exons are clustered into gene or isoform levels for quantification. The resulting data enables characterization of gene expression levels that can be applied to investigate distinct features of transcriptome diversity, including alternative splicing events, novel isoforms, and allele-specific expression [1].

Table 1: Comparison of Transcriptome Profiling Methods

| Feature | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing | 3' mRNA-Seq | Microarrays |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | High-throughput sequencing | High-throughput sequencing of 3' ends | Hybridization |

| Transcript Coverage | All RNA species (coding & non-coding) | Only polyadenylated mRNA | Pre-defined sequences only |

| Ability to Distinguish Isoforms | Yes | Limited | Limited |

| Dynamic Range | >8,000-fold | Limited by 3' end diversity | Few 100-fold |

| Required RNA Input | Low (nanograms) | Low (nanograms) | High (micrograms) |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Yes | No | No |

| Typical Read Depth | High (>25 million reads) | Lower (1-5 million reads) | Not applicable |

Comparison with Other Transcriptomic Approaches

When compared to other transcriptomic techniques, whole transcriptome sequencing offers several distinct advantages. Microarrays, which previously served as the most cost-effective and reliable method for high-throughput gene expression profiling, require a priori knowledge of sequences to be investigated, limiting discovery of novel exons, transcripts, and genes [1]. Additionally, hybridization-based methods used in microarrays can limit the dynamic range of gene expression quantification, casting doubt on measurements of transcripts with either very high or low abundance [1].

The distinction between whole transcriptome sequencing and 3' mRNA-Seq is equally important. While 3' mRNA-Seq provides a cost-effective approach for gene expression quantification by sequencing only the 3' ends of transcripts, it cannot detect non-coding RNAs (as most lack poly-A tails) or provide comprehensive information about alternative splicing and isoform-level expression [4]. Whole transcriptome sequencing, in contrast, offers a complete view of transcriptome complexity, making it indispensable for studies requiring discovery of novel transcripts, fusion genes, or comprehensive isoform characterization [4].

Key Applications in Research and Drug Development

Characterizing Transcriptome Diversity and Regulation

Whole transcriptome profiling enables researchers to investigate multiple dimensions of transcriptional regulation that are inaccessible with targeted approaches. One of the most powerful applications is the analysis of alternative splicing, a process that joins exons in different combinations to produce distinct mRNA isoforms from the same gene, dramatically expanding proteomic diversity [1] [5]. Up to 95% of multi-exon human genes undergo alternative splicing, which plays a key role in shaping biological complexity and is exceptionally susceptible to hereditary and somatic mutations associated with a broad range of diseases [1] [5]. RNA-Seq enables exploration of transcriptome structure with nucleotide-level resolution, allowing annotation of new exon-intron structures and detection of relative isoform abundance without relying on prior knowledge of transcriptome structure [1].

The technology also facilitates investigation of gene expression regulation by identifying expression quantitative trait loci (eQTLs)—genetic polymorphisms associated with variation in gene expression levels [1]. Most single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified through genome-wide association studies reside in non-coding or intergenic regions, suggesting that many causal variants influence phenotypes by impacting gene expression rather than protein structure [1]. Whole transcriptome profiling at single-nucleotide resolution enables detection of allele-specific expression (ASE), where one allele is expressed more highly than the other, signaling the presence of genetic or epigenetic determinants that influence transcriptional activity [1]. These regulatory mechanisms provide crucial insights into the molecular basis of disease susceptibility and potential variability in drug response.

Advancing Pharmacogenomics and Precision Medicine

In pharmacogenomics, whole transcriptome profiling reveals how gene expression patterns influence variable drug response, complementing genetic approaches that focus primarily on DNA sequence variations [1]. Gene expression represents the most immediate phenotype that can be associated with cellular conditions such as drug exposure or disease state [1]. Regulatory variants that govern gene expression are key mediators of overall phenotypic diversity and frequently represent causal mutations in pharmacogenomics [1].

By comparing transcriptomes across different conditions—such as drug-treated versus untreated cells, or diseased versus healthy tissues—researchers can identify candidate genes accounting for drug response variability [1]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding drug mechanisms of action, identifying biomarkers of drug response, and discovering novel therapeutic targets. The comprehensive nature of whole transcriptome analysis ensures that important regulatory mechanisms involving non-coding RNAs or alternative isoforms are not overlooked, providing a more complete understanding of the molecular networks governing drug efficacy and toxicity.

Enabling Spatial Transcriptomics and Clinical Applications

Recent technological advances have expanded whole transcriptome profiling to include spatial context within tissues. Emerging spatial profiling technologies enable high-plex molecular profiling while preserving the spatial and morphological relationships between cells [6]. For example, Digital Spatial Profiling with Whole Transcriptome Atlas assays allows quantification of entire transcriptomes in user-defined regions of interest within tissue sections [6]. This spatial dimension is crucial for understanding tissue organization, development, and pathophysiology, particularly in complex tissues like tumors where the microenvironment significantly influences gene expression patterns.

In clinical settings, whole transcriptome profiling has been successfully applied to formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples—the most common preservation method for pathological specimens [7]. Despite challenges with RNA degradation in FFPE material, studies have demonstrated that ribosomal RNA depletion methods yield transcriptome data with median correlations of 0.95 compared to fresh-frozen samples, supporting the clinical utility of FFPE-derived RNA [7]. This compatibility with archival clinical samples enables large-scale retrospective studies and facilitates the integration of transcriptomic data into clinical decision-making.

Table 2: Key Research Applications of Whole Transcriptome Profiling

| Application Domain | Specific Uses | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Research | Transcript discovery, isoform characterization, allele-specific expression | Elucidates fundamental biological mechanisms |

| Disease Mechanisms | Pathway analysis in diseased vs. normal tissues, biomarker discovery | Identifies molecular pathways underlying disease |

| Pharmacogenomics | Drug mechanism of action, toxicity prediction, response biomarkers | Guides personalized therapeutic approaches |

| Spatial Transcriptomics | Tumor heterogeneity, developmental biology, tissue organization | Preserves morphological context of gene expression |

| Agricultural Biology | Trait development, pigment formation, stress response [8] [3] | Improves breeding strategies and crop quality |

| Clinical Diagnostics | Cancer subtyping, fusion detection, expression signatures | Informs diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment selection |

Experimental Design and Methodological Considerations

Research Reagent Solutions and Experimental Workflow

Successful whole transcriptome profiling requires careful selection of research reagents and methodological approaches at each step of the experimental workflow. The following components are essential for generating high-quality transcriptome data:

- RNA Isolation Reagents: Specialized reagents that maintain RNA integrity while effectively removing contaminants. For tissues rich in RNases or complex matrices, additional stabilization or purification steps may be necessary.

- Ribosomal Depletion Kits: Commercial kits designed to remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA) which otherwise dominates sequencing libraries. These employ probes targeting species-specific rRNA sequences followed by magnetic bead-based removal.

- Library Preparation Kits: Strand-specific library preparation kits that convert RNA to cDNA while preserving information about the original transcriptional strand. These typically include fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification components.

- Quality Control Assays: Bioanalyzer or TapeStation reagents that assess RNA integrity (RIN) and library quality before sequencing, crucial for predicting sequencing success.

- Sequencing Reagents: Flow cells, polymerases, and nucleotides specific to the sequencing platform (e.g., Illumina, Ion Torrent) that enable high-throughput sequencing of prepared libraries.

The experimental workflow encompasses sample collection, RNA extraction, quality control, ribosomal depletion, library preparation, sequencing, and bioinformatic analysis. Each step requires optimization based on sample type and research objectives. For challenging samples such as FFPE tissues, specialized extraction protocols incorporating micro-homogenization or increased digestion times may be necessary to recover sufficient quality RNA [7].

Analytical Framework for Whole Transcriptome Data

The analytical workflow for whole transcriptome data involves multiple computational steps that transform raw sequencing reads into biological insights. After base calling and quality assessment, reads are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners that can handle reads spanning exon-exon junctions [1]. Following alignment, reads are assigned to genomic features (genes, exons, transcripts) and counted. Normalization methods account for technical variables such as transcript length and sequencing depth, with Reads/Fragments Per Kilobase per Million (R/FPKM) representing a commonly used normalized expression measure [1].

Downstream analyses include differential expression testing to identify genes or transcripts that vary between conditions, alternative splicing analysis to detect isoform ratio changes, and co-expression network analysis to identify functionally related gene modules. For studies integrating genetic data, expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) mapping identifies genetic variants associated with expression variation, while allele-specific expression analysis detects imbalances in allelic expression that may indicate functional regulatory variants [1] [5]. Functional interpretation typically involves gene set enrichment analysis to identify biological pathways, processes, or functions that are overrepresented among differentially expressed genes.

Whole transcriptome profiling represents a transformative approach for comprehensively characterizing transcriptional landscapes, enabling discoveries across diverse fields from basic biology to clinical research. By capturing both coding and non-coding RNA species, this methodology provides unprecedented insights into the complexity of gene regulation, including alternative splicing, allele-specific expression, and spatial organization of transcription. As technologies continue to advance—particularly in sensitivity, spatial resolution, and compatibility with challenging sample types—whole transcriptome profiling will play an increasingly central role in elucidating molecular mechanisms of disease, identifying therapeutic targets, and advancing personalized medicine. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastery of this powerful approach is essential for remaining at the forefront of genomic science and translational innovation.

The journey from a raw genome sequence to clinically actionable biomarkers represents a cornerstone of modern precision medicine. This process integrates genome annotation, which identifies functional elements within a DNA sequence, with network biology, which maps the complex interactions between these elements, to ultimately enable biomarker discovery for diagnosing diseases, predicting treatment responses, and developing new therapeutics [9]. Within the context of whole transcriptome profiling, this pipeline transforms massive, complex sequencing data into a coherent understanding of biological systems and their dysregulation in disease states. The transcriptome serves as a dynamic intermediary, reflecting the interplay between the static genome and the functional proteome, making it exceptionally valuable for identifying signatures of health and disease [1] [10]. This technical guide details the key objectives, methodologies, and experimental protocols that underpin this critical analytical pathway, providing a framework for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate from fundamental genomic sequence to clinically relevant insights.

Foundational Stage: High-Quality Genome Annotation

Genome annotation is the foundational process of identifying the location and function of genetic elements within a genome sequence. The quality of this initial stage is paramount, as errors here propagate through all subsequent analyses [11].

Key Objectives in Genome Annotation

- Structural Annotation: Identify the precise physical boundaries of genes, including exons, introns, and untranslated regions (UTRs).

- Functional Annotation: Assign biological roles to predicted genes, such as enzymatic functions or involvement in specific pathways, using databases like Gene Ontology (GO) and KEGG [12].

- Evidence Integration: Combine multiple types of supporting data, such as RNA-Seq reads, protein alignments, and ab initio predictions, to generate consensus, high-confidence gene models [13].

- Completeness Assessment: Evaluate the annotation using metrics like BUSCO to ensure a core set of evolutionarily conserved genes is present and complete [14] [11].

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

A robust annotation pipeline strategically integrates various types of evidence to overcome the limitations of any single method.

Table 1: Core Components of a Genome Annotation Pipeline

| Pipeline Stage | Key Tools & Technologies | Primary Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Preprocessing | FastQC, Trimmomatic | Assess and improve raw sequencing data quality. | Critical for reducing artifacts and mis-assemblies. |

| Evidence Alignment | STAR [14], Minimap2 [14], StringTie [11] | Align RNA-Seq and long-read transcriptome data to the genome. | Provides direct evidence of transcribed regions and splice sites. |

| Gene Prediction | AUGUSTUS [11], BRAKER [11], MAKER2 [11] | Predict gene models using aligned evidence and/or ab initio algorithms. | Combining evidence-based and ab initio approaches yields the best results. |

| Functional Annotation | BLAST, InterProScan [14] [12], Diamond [14] | Assign functional terms based on sequence homology and domain architecture. | Relies on curated databases, which can be incomplete for non-model organisms. |

| Validation & QC | BUSCO [14] [11], GeneValidator [11] | Benchmark annotation completeness and identify problematic models. | Essential for estimating the reliability of the final annotation. |

For non-model organisms or those with limited genomic resources, a modular pipeline that combines de novo and reference-based assembly, as demonstrated in the SmedAnno pipeline for Schmidtea mediterranea, can reveal thousands of novel genes and improve existing models [13]. Furthermore, the NCBI Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline (EGAP) exemplifies continuous improvement, with recent versions incorporating advancements such as:

- Automated computation of maximum intron length for alignment tools [14].

- Assignment of Gene Ontology terms via InterProScan [14].

- Generation of normalized gene expression counts from RNA-Seq data [14].

- Enhanced handling of long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore [14].

Figure 1: A typical genome annotation workflow, illustrating the progression from raw sequence data to a validated, functionally annotated genome.

Bridging Stage: Network Biology and Pathway Analysis

Network biology provides the conceptual framework to move from a static list of annotated genes to a dynamic understanding of their functional interactions. It views cellular processes as interconnected webs, where perturbations in one node can ripple through the entire system [15].

Key Objectives in Network Biology

- Contextualize Gene Function: Understand genes not in isolation, but within their functional modules and pathways.

- Identify Key Regulators: Pinpoint hub genes that occupy central positions in networks and are often critical for network stability and function.

- Uncover Mechanistic Insights: Generate hypotheses about the underlying mechanisms of disease or drug response by analyzing perturbed networks.

- Integrate Multi-Omics Data: Overlay transcriptomic, proteomic, and metabolomic data onto interaction networks to build a more comprehensive model of biology.

Methodologies for Network Construction and Analysis

Network-based models leverage protein-protein interaction (PPI) data and curated pathway databases to analyze high-throughput transcriptomic data.

The PathNetDRP Framework: A novel approach for biomarker discovery exemplifies the power of network biology. It integrates PPI networks, biological pathways, and gene expression data from transcriptomic studies to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) [15]. Its methodology involves:

- Candidate Gene Prioritization: Application of the PageRank algorithm on a PPI network, initialized with known ICI target genes, to identify biologically relevant candidate genes associated with drug response [15].

- Pathway Identification: Statistical enrichment analysis (e.g., hypergeometric test) of the prioritized genes against pathway databases to identify ICI-response-related pathways [15].

- Gene Scoring: Calculation of a "PathNetGene" score by applying PageRank to pathway-specific subnetworks, quantifying the contribution of each gene within its biological context [15].

This framework demonstrates that network-based biomarkers can achieve superior predictive performance (AUC of 0.940 in validation studies) compared to models relying solely on differential gene expression [15].

Figure 2: The PathNetDRP framework integrates transcriptome data with network biology to identify functionally relevant biomarkers.

Application Stage: Biomarker Discovery in Drug Development

The ultimate application of the annotation-to-network pipeline is the discovery and validation of biomarkers. In drug discovery and development, biomarkers are used to understand disease mechanisms, identify drug targets, predict patient response, and assess toxicity [16] [9] [17].

Key Objectives in Biomarker Discovery

- Target Identification: Pinpoint genes or pathways whose activity is crucial to a disease, representing potential points of therapeutic intervention [16].

- Stratification Biomarkers: Identify molecular signatures that can segment patient populations into likely responders and non-responders to a specific therapy.

- Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers: Measure the biological effects of a drug on its target, providing early evidence of mechanism of action.

- Resistance Biomarkers: Uncover mechanisms, such as alternative splicing or expression of drug efflux pumps, that lead to treatment failure [16].

Transcriptome-Driven Methodologies for Biomarker Discovery

Whole transcriptome sequencing serves as a primary tool for biomarker discovery by providing an unbiased view of all coding and non-coding RNAs in a sample [10].

Table 2: Applications of Transcriptome Profiling in Biomarker Discovery and Drug Development

| Application Area | Methodology | Output | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA Profiling | Bulk RNA-Seq of diseased vs. normal tissue. | Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) as candidate biomarkers. | Identifying oncogene-driven transcriptome profiles for cancer therapy targets [16]. |

| Alternative Splicing Analysis | Junction-spanning RNA-Seq read analysis. | Detection of disease-specific splice variants as biomarkers. | Revealing tissue-specific splicing factors and regulatory elements [1]. |

| Drug Repurposing | Transcriptome profiling of primary disease specimens treated with existing drugs. | Identification of novel therapeutic indications. | Screening in Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML) revealed efficacy of Mubritinib, a breast cancer drug [16]. |

| Pharmacogenomics | Correlation of transcriptome profiles with drug response data. | Expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs) and gene signatures for drug response. | Optimizing drug dosages to maximize efficacy and minimize side effects [1] [16]. |

| Single-Cell Profiling | scRNA-Seq of tumor microenvironments. | Identification of cell-type-specific biomarkers and drug targets. | DeepGeneX model reduced 26,000 genes to six key genes in macrophage populations [15] [9]. |

Overcoming Challenges with Time-Resolved Transcriptomics: A significant challenge in drug discovery is distinguishing the primary, direct effects of a drug from secondary, indirect effects on the transcriptome. Time-resolved RNA-Seq addresses this by profiling RNA abundances at multiple time points after drug treatment. Techniques like SLAMseq enable the investigation of RNA kinetics, allowing researchers to resolve complex regulatory networks and more accurately identify direct drug targets [16].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Solutions

Successful execution of the pipeline from genome annotation to biomarker discovery relies on a suite of well-established reagents, software tools, and databases.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Transcriptome-Based Discovery

| Category / Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA from total RNA samples. | Enriches for coding and non-coding RNA of interest in whole transcriptome sequencing [10]. |

| Strand-Specific cDNA Library Prep Kits | Preserves the original orientation of RNA transcripts during cDNA synthesis. | Allows accurate determination of transcription from sense vs. antisense strands. |

| Single-Cell RNA Barcoding Reagents | Tags cDNA from individual cells with unique molecular identifiers (UMIs). | Enables multiplexing and tracing of transcripts back to their cell of origin in scRNA-Seq [9]. |

| Automated Sample Prep Systems | Standardizes and scales up RNA library preparation for transcriptomics. | Enables high-throughput processing of hundreds of samples for large cohort studies [17]. |

| Reference Transcriptomes | Curated sets of known transcripts for an organism (e.g., RefSeq). | Serves as a reference for RNA-Seq read alignment and expression quantification [14]. |

| Pathway Analysis Software | Tools for statistical enrichment analysis of gene lists. | Identifies biological pathways significantly enriched in a set of differentially expressed genes. |

| Interaction Network Databases | Databases of known protein-protein and genetic interactions (e.g., STRING). | Provides the scaffold for constructing functional biological networks for analysis [15]. |

The integrated pathway from high-quality genome annotation through context-aware network biology to functionally validated biomarker discovery creates a powerful engine for scientific and clinical advancement. As technologies evolve—including the incorporation of long-read sequencing for more accurate annotation, the application of artificial intelligence for network analysis, and the rise of microsampling for decentralized biomarker profiling—this pipeline will only increase in its resolution, efficiency, and translational impact [14] [17]. For researchers and drug developers, mastering the key objectives, methodologies, and tools outlined in this guide is essential for harnessing the full potential of whole transcriptome data to drive the next generation of personalized medicine.

The comprehensive analysis of the transcriptome, the complete set of RNA transcripts within a cell, is fundamental to understanding functional genomics, cellular responses, and the molecular mechanisms underlying disease and drug response [1]. The evolution of technologies for profiling this transcriptome, from the early expressed sequence tag (EST) sequencing to contemporary high-throughput next-generation sequencing (NGS), represents a paradigm shift in biological research [18] [1]. This progression has been driven by the need to move beyond static genomic information to a dynamic view of gene expression, which reflects the immediate phenotype of a cell and is influenced by genetic variation, cellular conditions, and environmental factors [1]. Framed within the context of whole transcriptome profiling, this technical guide details the core methodologies, their experimental protocols, and their transformative impact on biomedical research and drug development.

Historical Foundations: EST and Sanger Sequencing

The journey into transcriptome analysis began with Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) sequencing, a methodology reliant on the Sanger sequencing platform. ESTs are short, single-pass sequence reads (typically <500 base pairs) derived from the 5' or 3' ends of complementary DNA (cDNA) clones [18].

Core Methodology of EST Sequencing

The experimental workflow for generating ESTs involved several key steps [18]:

- cDNA Library Construction: mRNA was isolated from a biological sample and reverse-transcribed into a library of cDNA clones.

- Clone Picking and Sequencing: Individual cDNA clones were picked and subjected to Sanger sequencing, which used dideoxynucleotides (ddNTPs) as chain-terminating inhibitors [18].

- Fragment Separation and Reading: The resulting DNA fragments, originally separated by size using gel electrophoresis and detected with radioactive labels, were later automated using capillary electrophoresis and fluorescent dyes [18].

- Sequence Compilation: A computer program interpreted the fluorescent traces and compiled the sequence, enabling the identification of new genes by matching EST sequences to existing databases [18].

Limitations and Legacy

EST sequencing was a groundbreaking tool for gene discovery, famously contributing to the identification of genes linked to human diseases like Huntington's [18]. However, its limitations were significant: it was relatively low-throughput, costly, and time-consuming [18]. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) maintains an EST database that continues to serve as a historical gene discovery tool [18].

Table 1: Comparison of Sequencing Eras

| Feature | Sanger/EST Sequencing | Next-Generation Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Low (a few hundred base pairs in days) [18] | Very High (millions/billions of reads in a run) [18] |

| Read Length | Long (<1 kilobase) [18] | Short (initially 30-500 bp) to Long (>10 kb) [1] [18] |

| Cost (Human Genome) | ~$1 billion [18] | ~$100,000 (circa 2005) and falling [18] |

| Key Technology | Chain-terminating ddNTPs [18] | Massive parallel sequencing [18] |

| Primary Application | Gene discovery, individual gene sequencing [18] | Whole genomes, transcriptomes, epigenomics [18] |

The Next-Generation Sequencing Revolution

Next-generation sequencing (NGS), or high-throughput sequencing, transformed genomics by enabling the massive parallel sequencing of DNA fragments, drastically reducing both cost and time [18]. A key technological advance was the development of reversible dye terminator technology, which allowed for the addition of a single nucleotide at a time during DNA synthesis, followed by fluorescence imaging and chemical cleavage of the terminator to enable the next cycle of incorporation [18]. This core principle is shared by several major NGS platforms.

Key NGS Platform Technologies

The following dot script outlines the core decision points and workflows for establishing an NGS-based transcriptome profiling project.

- 454/Roche GS FLX Titanium: This was the first commercially available NGS platform (2005) and was based on pyrosequencing [18]. This technique detects nucleotide incorporation in real-time by measuring the light generated when a released pyrophosphate (PPi) is converted to ATP, which then drives a luciferase reaction [18]. DNA fragments were amplified on beads via emulsion PCR, and the platform was capable of longer reads than some competitors, completing a human genome in about two months in 2005 [18].

- Illumina (Solexa) Sequencing: Illumina platforms became the dominant technology, utilizing a reversible dye terminator method [18]. Library preparation uses bridge amplification on a flow cell, where DNA fragments bend over and hybridize to complementary oligonucleotides to form clusters [18]. The sequencing-by-synthesis process involves cyclical nucleotide addition, fluorescence imaging, and terminator cleavage, generating vast amounts of short-read data [18].

- SOLiD Sequencing: The Supported Oligonucleotide Ligation and Detection (SOLiD) system employed a different biochemistry based on sequential ligation of fluorescently labeled di-base probes [18]. This method sequenced DNA two nucleotides at a time, which provided inherent error-checking capability [19].

- Ion Torrent: This platform also used emulsion PCR but adopted a semiconductor-based approach, detecting the pH change that occurs when a nucleotide is incorporated into a growing DNA strand, rather than using optics [18].

NGS in Whole Transcriptome Profiling

The application of NGS to RNA, known as RNA-Seq, has emerged as the premier method for transcriptome analysis, superseding microarrays [1].

RNA-Seq Methodology and Workflow

A standard RNA-Seq workflow involves the following key experimental steps [1] [10]:

- RNA Extraction and Quality Control: Total RNA is isolated from the sample. RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a critical quality metric.

- Library Preparation: The population of input RNA (total RNA or fractionated) is converted into a sequencing library.

- Target Enrichment (if applicable): Two primary strategies are used:

- Poly(A) Enrichment: Captures messenger RNAs (mRNAs) with poly-A tails, focusing on protein-coding genes [20].

- rRNA Depletion: Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), allowing for sequencing of the remaining RNA, including both coding and non-coding species (the basis of Whole Transcriptome Sequencing) [10] [20].

- High-Throughput Sequencing: The library is amplified and sequenced on an NGS platform, generating millions of short reads.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Reads are computationally mapped to a reference genome or transcriptome. Overlapping reads are clustered, and gene expression is quantified using normalized metrics like FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of exon model per Million mapped reads) [1]. Subsequent analyses identify differentially expressed genes, alternative splicing events, and other features.

Table 2: Comparison of RNA-Seq Methodologies

| Parameter | mRNA Sequencing (mRNA-Seq) | Whole Transcriptome Sequencing (WTS) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Poly(A) enrichment of mRNA [20] | rRNA depletion from total RNA [10] [20] |

| Transcripts Captured | Primarily poly-adenylated mRNA [20] | All RNA species: coding mRNA and non-coding RNA (lncRNA, circRNA, miRNA) [10] [20] |

| Required RNA Input | Low (nanograms) [20] | Higher (≥ 500ng total RNA) [21] [20] |

| Sequencing Depth | Lower (25-50 million reads/sample) [20] | Higher (100-200 million reads/sample) [20] |

| Ideal For | Differential expression of known protein-coding genes [22] | Discovery of novel transcripts, non-coding RNA, full splice variants [22] [10] |

| Cost | Generally lower [20] | Generally higher [20] |

Advantages of RNA-Seq over Microarrays

RNA-Seq provides a significant qualitative and quantitative improvement over earlier hybridization-based microarray technologies [1].

Table 3: RNA-Seq vs. Microarrays

| Feature | Microarrays | RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Hybridization [1] | High-throughput sequencing [1] |

| Background Noise | High [1] | Low [1] |

| Dynamic Range | Few 100-fold [1] | >8,000-fold [1] |

| Reliance on Genomic Sequence | Yes (requires pre-designed probes) [1] | Not necessarily [1] |

| Ability to Distinguish Isoforms | Limited [1] | Yes [1] |

| Ability to Detect Novel Transcripts | No [1] | Yes [1] |

Advanced Applications and Cutting-Edge Innovations

The resolution of NGS has enabled sophisticated applications that are integral to modern drug development and biomedical research.

Key Research Applications

- mRNA Expression Profiling: The comparison of transcriptomes across conditions (e.g., diseased vs. normal) to identify differentially expressed genes key to disease mechanisms or drug response [1].

- Alternative Splicing Analysis: RNA-Seq allows for the exploration of transcriptome structure and the detection of different patterns of splice junctions with high accuracy, revealing a previously unprecedented diversity of splice variants linked to disease [1].

- Allele-Specific Expression (ASE): The single-nucleotide resolution of RNA-Seq enables investigators to detect imbalances in the expression of two alleles in heterozygous individuals, signaling the presence of genetic or epigenetic regulatory elements [1].

- Biomarker Discovery: Comprehensive transcriptome profiling is invaluable for identifying RNA signatures for cancer classification, treatment response prediction, and neurodegenerative disease characterization [21].

Emerging Technologies and Recent Advances

The field of transcriptomics continues to evolve rapidly with several groundbreaking technologies:

- Long-Read Sequencing (Roche SBX & Nanopore): Newer technologies address the short-read limitation of early NGS by producing read lengths >10 kb, simplifying genome assembly and improving the detection of structural variations [18]. Roche's recently unveiled Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology, for instance, combines speed, flexibility, and longer reads, and was used to set a GUINNESS WORLD RECORD for the fastest DNA sequencing technique (from sample to variant call in under four hours) [23].

- Direct RNA Sequencing (Nanopore): Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enables direct sequencing of native RNA molecules without cDNA conversion. This allows for the simultaneous detection of transcript isoforms and epitranscriptomic modifications (e.g., m6A), capturing a more complete picture of the RNA molecule [24].

- Spatial Transcriptomics: Technologies like Bruker's CosMx Whole Transcriptome Assay allow for highly detailed, subcellular imaging of nearly the entire human protein-coding transcriptome within intact tissue samples (FFPE), preserving the crucial spatial context of gene expression [19].

- Multi-Omics Integration: A major trend is the convergence of sequencing data types. For example, Roche's SBX technology is being applied to combine rapid sequencing with the analysis of methylation maps (epigenomics) and gene expression (transcriptomics) to redefine the interpretation of disease biology [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of a whole transcriptome study requires careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table details key components.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Whole Transcriptome Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Selective removal of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA to enrich for coding and non-coding RNAs of interest. [10] [20] | Critical for WTS. Efficiency directly impacts sequencing sensitivity and cost. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preserves the original orientation of the RNA transcript during cDNA library construction, allowing determination of which DNA strand was transcribed. [20] | Essential for accurately annotating overlapping genes and non-coding RNAs. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short, random nucleotide sequences ligated to each RNA molecule before amplification, enabling accurate digital quantification and removal of PCR duplicates. [21] | Dramatically improves quantification accuracy, especially for low-abundance transcripts. |

| Methylation Mapping Kits (e.g., TAPS) | High-fidelity methods for identifying and analyzing DNA methylation, an key epigenetic modification, which can be combined with sequencing. [23] | Enables integrative multi-omics analysis of genetics and epigenetics. |

| Spatial Barcoding Oligonucleotides | Barcoded probes used in spatial transcriptomics to hybridize to RNA targets in situ, linking transcript identity to spatial coordinates in a tissue section. [19] | Required for any spatial transcriptomics workflow to preserve location data. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Enzyme used during library amplification for accurate replication of cDNA fragments with minimal introduction of errors. | Ensures high sequencing data fidelity and reduces artifacts. |

The evolution from EST sequencing to modern NGS platforms has fundamentally transformed our capacity to interrogate the transcriptome. This journey, marked by orders-of-magnitude improvements in throughput, cost, and resolution, has made comprehensive whole transcriptome profiling an accessible and powerful tool for researchers and drug developers. The ability to dynamically profile not just, not only coding genes but also the vast realm of non-coding RNAs and splice variants, provides an immediate and deep phenotype that is bridging the gap between genomics and clinical outcomes. As technologies like long-read sequencing, direct RNA analysis, and spatial transcriptomics continue to mature and integrate, they promise to further refine our understanding of biology and accelerate the pace of discovery in precision medicine.

The transcriptome represents the complete set of RNA transcripts, including multiple RNA species, produced by the genome in a specific cell or tissue at a given time. This dynamic entity extends far beyond messenger RNA (mRNA) to encompass a diverse array of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) that play crucial regulatory roles, fundamentally shifting our understanding of gene regulation, cellular plasticity, and disease pathogenesis [25]. While every human cell contains the same genetic information, the carefully controlled pattern of gene expression differentiates cell types and states, making transcriptome analysis the most immediate phenotype that can be associated with cellular conditions [1].

High-throughput sequencing technologies have revolutionized our ability to characterize transcriptome diversity, moving from hybridization-based microarrays to comprehensive RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) that enables both transcript discovery and quantification in a single assay [1] [9]. These advances have revealed that less than 2% of the human genome encodes proteins, while the vast majority is transcribed into ncRNAs that play diverse and crucial roles in cellular function [26]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of the core components of the transcriptome, their functional mechanisms, and the experimental frameworks for their study.

Core Components of the Transcriptome

Messenger RNA (mRNA)

Messenger RNA (mRNA) serves as the crucial intermediary that carries genetic information from DNA in the nucleus to the ribosomes in the cytoplasm, where it directs protein synthesis. These protein-coding RNAs represent one of the most extensively studied transcriptome components, with their expression levels reflecting the combined influence of genetic factors, cellular conditions, and environmental influences [1].

A critical layer of mRNA complexity arises from alternative splicing, where exons are joined in different combinations to produce distinct mRNA isoforms from the same gene. Recent advances in sequencing technologies have revealed that up to 95% of multi-exon genes undergo alternative splicing in humans, dramatically expanding proteomic diversity beyond the ~20,000 protein-coding genes [5]. Additional mechanisms generating mRNA diversity include alternative transcription start sites and alternative polyadenylation sites, all contributing to the remarkable complexity of the protein-coding transcriptome [5].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Messenger RNA (mRNA)

| Property | Description | Functional Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Coding Capacity | Contains open reading frame (ORF) for protein translation | Directs synthesis of proteins essential for cellular structure and function |

| Structural Features | 5' cap, 5' UTR, coding region, 3' UTR, poly-A tail | Facilitates nuclear export, translation efficiency, and stability regulation |

| Isoform Diversity | Generated via alternative splicing, start sites, polyadenylation | Expands proteomic diversity from limited gene set; enables tissue-specific functions |

| Regulation | Subject to transcriptional and post-transcriptional control | Allows dynamic response to cellular signals and environmental changes |

| Abundance | Varies from few to thousands of copies per cell | Enables precise control of protein expression levels |

Long Non-Coding RNA (lncRNA)

Long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) are defined as RNA transcripts longer than 200 nucleotides that lack significant protein-coding potential. Once considered transcriptional "noise," lncRNAs are now recognized as crucial regulators of gene expression at multiple levels [25]. The field has moved beyond simplistic uniform descriptions, recognizing lncRNAs as diverse ribonucleoprotein scaffolds with defined subcellular localizations, modular secondary structures, and dosage-sensitive activities that often function at low abundance to achieve molecular specificity [25].

Mechanistically, lncRNAs employ several functional paradigms:

- Chromatin modification: LncRNAs recruit and scaffold epigenetic modifiers to specific genomic loci, enabling targeted histone modification and DNA methylation [25].

- Transcriptional regulation: They act as guides, decoys, or scaffolds to modulate transcription factor activity and RNA polymerase II recruitment [25].

- Nuclear organization: Certain lncRNAs contribute to the formation and maintenance of nuclear subdomains and paraspeckles.

- Post-transcriptional processing: They influence splicing, stability, and translation of other RNA transcripts.

Table 2: Functional Mechanisms of Long Non-Coding RNAs

| Mechanism | Molecular Function | Biological Example |

|---|---|---|

| Scaffolding | Assembly of ribonucleoprotein complexes | X-chromosome inactivation by Xist lncRNA |

| Guide | Directing ribonucleoprotein complexes to specific genomic loci | Epigenetic regulation by HOTAIR |

| Decoy | Sequestration of transcription factors or miRNAs | PANDA lncRNA sequesters transcription factors |

| Enhancer | Facilitating enhancer-promoter interactions | eRNA-mediated chromatin looping |

| Signaling | Molecular sensors of cellular signaling pathways | LncRNAs responding to DNA damage |

Circular RNA (circRNA)

Circular RNAs (circRNAs) represent a unique class of covalently closed RNA molecules generated through a non-canonical splicing event known as back-splicing, where a downstream splice donor site joins an upstream splice acceptor site [26]. This circular conformation provides exceptional stability compared to linear RNAs due to resistance to exonuclease-mediated degradation. Initially discovered as viral RNAs or splicing byproducts, circRNAs gained significant attention with the advancement of high-throughput sequencing and specialized computational pipelines [26].

The functional repertoire of circRNAs has expanded considerably beyond their original characterization as miRNA sponges:

- miRNA sponging: Some circRNAs contain multiple binding sites for specific microRNAs, sequestering them and preventing their interaction with target mRNAs [25] [27].

- Protein binding: CircRNAs can function as protein scaffolds or decoys, modulating protein function, localization, and stability [25] [26].

- Translation capacity: Contrary to initial classification as non-coding, some circRNAs can be translated into proteins or micropeptides via cap-independent mechanisms, particularly those containing internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) or N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modifications [25] [27].

- mRNA regulators: Emerging evidence demonstrates direct circRNA-mRNA interactions that influence mRNA stability and translation, representing a novel layer of post-transcriptional regulation [26].

Diagram: Multifunctional Roles of circRNAs in Gene Regulation. circRNAs employ diverse mechanisms including miRNA sponging, protein scaffolding, direct mRNA regulation, and translation into functional peptides.

Additional Transcriptome Components

Beyond these major categories, the transcriptome includes several other specialized RNA classes:

- MicroRNAs (miRNAs): Short (~22 nt) non-coding RNAs that regulate gene expression through post-transcriptional silencing by binding to target mRNAs, leading to translational repression or degradation [25] [16].

- Transfer RNAs (tRNAs): Adaptor molecules that deliver specific amino acids to the ribosome during protein translation.

- Ribosomal RNAs (rRNAs): Structural and catalytic components of the ribosome, representing the most abundant RNA species in most cells.

- Enhancer RNAs (eRNAs): Short, unstable non-coding RNAs transcribed from enhancer regions that contribute to enhancer function [28].

Table 3: Quantitative Comparison of Major Transcriptome Components

| RNA Class | Size Range | Cellular Abundance | Stability | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | 0.5-10+ kb | Highly variable | Moderate (hours-days) | Protein coding |

| lncRNA | 0.2-100+ kb | Generally low | Variable | Chromatin regulation, scaffolding |

| circRNA | 100-4000 nt | Variable, often tissue-specific | High (days+) | miRNA sponging, translation, scaffolds |

| miRNA | 20-25 nt | Variable | Moderate | Post-transcriptional repression |

| eRNA | 0.1-9 kb | Very low | Low (minutes) | Enhancer function |

Experimental Approaches for Transcriptome Analysis

Whole Transcriptome Profiling Technologies

The evolution of transcriptomic technologies has progressively enhanced our ability to characterize RNA populations with increasing resolution and comprehensiveness:

- Gene Expression Microarrays: Hybridization-based technology that enables parallel quantification of predefined transcripts using fluorescently labeled probes [1] [9]. While limited to detecting known sequences, microarrays offer high throughput, rapid analysis, and established validation pipelines [9].

- RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq): A transformative next-generation sequencing approach that enables comprehensive transcriptome characterization without prerequisite sequence knowledge [1]. RNA-Seq provides a significantly broader dynamic range (>8,000-fold) compared to microarrays (few 100-fold), enables distinction of alternative isoforms, and permits detection of novel transcripts, all at single-base resolution [1].

- Single-Cell RNA Sequencing (scRNA-seq): Represents a revolutionary advancement that enables transcriptome profiling at individual cell resolution, revealing cellular heterogeneity inaccessible to bulk tissue analysis [29]. This approach includes both whole transcriptome and targeted gene expression methods, each with distinct advantages [29].

- Nascent Transcript Sequencing: Specialized methods like PRO-seq (Precision Run-On Sequencing) and its recent advancement rPRO-seq (rapid PRO-seq) map transcriptionally engaged RNA polymerase with nucleotide resolution, capturing unstable and low-abundance nascent transcripts that conventional RNA-Seq misses [28].

Diagram: Experimental Workflow for Transcriptome Profiling Technologies. Multiple approaches enable transcriptome characterization at different resolutions, from bulk tissue analysis to single-cell and nascent transcript mapping.

Specialized Methodologies for RNA-RNA Interaction Mapping

Understanding the functional networks within the transcriptome requires technologies that capture the complex interactions between different RNA species:

- Protein-Centric Methods: Approaches including CLASH, MARIO, RIC-seq, AGO-CLIP, hiCLIP, and PIP-seq immunoprecipitate crosslinked ribonucleoprotein complexes to identify RNA-RNA interactions mediated by specific RNA-binding proteins [26].

- RNA-Centric Strategies: Techniques such as PARIS, LIGR-seq, and SPLASH utilize psoralen crosslinking to stabilize native RNA-RNA interactions directly, followed by proximity ligation and sequencing to map base-paired regions [26].

- Functional Validation: Following identification of potential interactions, researchers employ antisense oligonucleotides (e.g., LNA-modified) to disrupt specific RNA-RNA pairs and assess functional consequences [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Transcriptome Analysis

| Reagent/Category | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Poly-A Selection Beads | Enrichment of polyadenylated transcripts | mRNA sequencing, library preparation |

| RNase Inhibitors | Protection against RNA degradation | Sample processing, cDNA synthesis |

| Reverse Transcriptase | cDNA synthesis from RNA templates | RNA-Seq library construction, RT-qPCR |

| Crosslinking Reagents | Stabilization of molecular interactions | CLIP-based methods, RNA-protein crosslinking |

| Barcoded Adapters | Sample multiplexing & identification | High-throughput sequencing |

| Antisense Oligonucleotides | Targeted RNA perturbation | Functional validation (e.g., LNA GapmeRs) |

| rPRO-seq Components | Nascent transcript profiling | P-3' App-DNA adapters, dimer-blocking oligos |

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Transcriptome analysis has become integral throughout the drug development pipeline, from initial target discovery to clinical application:

- Target Identification and Validation: RNA-Seq helps uncover genes and pathways playing important roles in disease by detecting differentially expressed transcripts and revealing new molecular mechanisms [16]. Single-cell whole transcriptome sequencing enables de novo cell type identification and uncovering of novel disease pathways in heterogeneous tissues [29].

- Biomarker Discovery: Transcriptome profiling identifies expression signatures correlating with disease presence, progression, or therapeutic response [9] [16]. Circular RNAs are particularly promising biomarkers due to their stability and frequent dysregulation in pathological conditions like cancer [27].

- Mechanism of Action Elucidation: Targeted gene expression panels provide highly sensitive readouts of drug activity on intended pathways while simultaneously screening for potential off-target effects [29]. Time-resolved RNA-Seq approaches like SLAMseq enable distinction between primary (direct) and secondary (indirect) drug effects by observing RNA kinetics [16].

- Overcoming Drug Resistance: RNA-Seq identifies genes and regulatory networks associated with treatment failure, enabling development of combination strategies to circumvent resistance mechanisms [25] [16]. For example, restoring tumor-suppressive miR-142-3p can overcome tyrosine-kinase-inhibitor resistance in hepatocellular carcinoma by coordinating multiple nodes in resistance pathways [25].

The transcriptome represents a dynamic and complex network of coding and non-coding RNA molecules that collectively orchestrate cellular function. The core components—mRNA, lncRNA, circRNA, and other regulatory RNAs—interconnect through multilayered regulatory systems that rewire cells in development, stress, and pathology [25]. Rapidly advancing technologies for transcriptome mapping continue to refine our understanding of these components, revealing an increasingly sophisticated regulatory landscape.

The field is progressing toward precision engineering of RNA biology, integrating single-cell and spatial transcriptomics with targeted RNA-protein crosslinking to sharpen functional maps of ncRNA activity [25]. As these technologies mature and therapeutic applications advance, transcriptome analysis will continue to drive innovations in disease mechanism understanding, biomarker development, and targeted therapeutic interventions across the spectrum of human disease.

From Lab to Insight: Methodologies and Real-World Applications

Whole transcriptome profiling via RNA Sequencing (RNA-Seq) has revolutionized the study of gene expression, enabling researchers to capture a snapshot of cellular processes by identifying and quantifying RNA transcripts present in a biological sample at a specific time [30] [31]. This comprehensive approach provides invaluable insights into changes in the transcriptome in response to environmental stimuli, disease states, or therapeutic interventions, allowing for the detection of mRNA splicing variants, single nucleotide polymorphisms, and novel transcriptional events [30]. Unlike microarrays, which require a known template and are notoriously unreliable for detecting low and very high abundance RNAs, RNA-Seq offers an unbiased platform for transcriptome-wide discovery [30]. The core of this technology involves converting RNA into complementary DNA (cDNA) through reverse transcription, followed by high-throughput sequencing of the resulting cDNA library [30] [31]. This technical guide details the standard workflow from RNA isolation to cDNA library preparation, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the foundational protocols essential for robust whole transcriptome analysis.

RNA Isolation and Quality Control

RNA Extraction and Integrity Preservation

The success of any RNA-Seq experiment is critically dependent on the quality and integrity of the starting RNA material. Maintaining RNA integrity requires special precautions during extraction, processing, storage, and experimental use [32]. Best practices to prevent RNA degradation include wearing gloves, pipetting with aerosol-barrier tips, using nuclease-free labware and reagents, and thorough decontamination of work areas [32] [30]. Optimal purification methods must also remove common inhibitors that interfere with the activity of reverse transcriptases, including both endogenous compounds from biological sample material and inhibitory carryover compounds from RNA isolation reagents, such as salts, metal ions, ethanol, and phenol [32].

RNA should be extracted from tissues using established methods (e.g., trizol-based extraction), with special consideration for the source materials (e.g., blood, tissues, cells, plants) and experimental goals [32] [30]. For cell cultures, most cells should be in the same stage of growth, and harvesting should occur quickly with minimal osmotic or temperature shock. Flash freezing and grinding the resulting powder in liquid nitrogen is a preferred method to achieve minimally damaged nucleic acids [30]. Once purified, RNA should be stored at –80°C with minimal freeze-thaw cycles to preserve stability [32].

RNA Quality Assessment and Genomic DNA Removal

After RNA extraction, checking RNA integrity is critical before proceeding with library preparation. The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) determined by the RIN algorithm provides a standardized measure of RNA quality, ranging from 10 (intact) to 1 (completely degraded) [30]. Samples with RIN values below 7 should generally not be used for RNA-Seq, as there is little point in working with degraded RNA [30].

A crucial step in sample preparation is the removal of trace genomic DNA (gDNA) that may be co-purified with RNA, as contaminating gDNA can interfere with reverse transcription and lead to false positives, higher background, or lower detection sensitivity in downstream applications like RT-qPCR [32]. The traditional method involves adding DNase I to preparations of isolated RNA; however, DNase I must be thoroughly removed prior to cDNA synthesis since any residual enzyme would degrade single-stranded DNA and compromise results [32]. As an alternative, double-strand-specific DNases (e.g., Invitrogen ezDNase Enzyme) offer advantages by eliminating contaminating gDNA without affecting RNA or single-stranded DNAs. These thermolabile enzymes enable simpler protocols with inactivation at relatively mild temperatures (e.g., 55°C) without the RNA loss or damage associated with DNase I inactivation methods [32].

Table 1: RNA Quality Assessment Metrics

| Parameter | Optimal Value/Range | Importance |

|---|---|---|

| RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | ≥7 [30] | Indicates overall RNA degradation level; critical for library complexity |

| 260/280 Ratio | ~2.0 | Assesses protein contamination |

| 260/230 Ratio | >2.0 | Detects contaminants like salts, carbohydrates |

| Genomic DNA Contamination | Not detectable | Prevents false positives and background noise in sequencing [32] |

| Total Quantity | Varies by protocol (e.g., ≥200 ng for SHERRY [33]) | Ensures sufficient material for library preparation |

RNA Selection and cDNA Synthesis

RNA Selection and Enrichment Strategies

Following quality control, the total RNA often requires selection or enrichment of specific RNA types depending on the research objectives. A key consideration is the removal of ribosomal RNA (rRNA), which constitutes approximately 90% of total RNA and would otherwise drown out the signal from other RNA species [30]. The simplest approach is to use commercial rRNA removal kits such as the NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit or Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit [30].

Further RNA selection depends on the specific goals of the study:

- Mature mRNA Isolation: For studies focusing on protein-coding genes or splice variants, mature mRNA can be isolated using the polyA tails that bind to poly(T) oligomers attached to beads [30].

- Small RNA Enrichment: For investigation of small RNAs such as miRNA, size selection through gel filtration or affinity chromatography is typically employed [30].

- Targeted RNA Capture: Specific transcripts of interest can be enriched through hybridization with tailored probes [30].

The choice of tissue or cell type is also critical, as the expression of relevant genes must be detectable in the chosen material. For instance, in neurodevelopmental disorders, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) express up to 80% of genes in intellectual disability and epilepsy panels, making them a suitable and minimally invasive source [34].

Reverse Transcription and cDNA Synthesis

The synthesis of cDNA from an RNA template through reverse transcription is a crucial first step in many molecular biology protocols, serving as the foundation for downstream applications [32]. This process creates complementary DNA (cDNA) that can then be used as template in a variety of RNA studies [32].

Reverse Transcriptase Selection: Most reverse transcriptases used in molecular biology are derived from the pol gene of avian myeloblastosis virus (AMV) or Moloney murine leukemia virus (MMLV) [32]. The AMV reverse transcriptase possesses strong RNase H activity that degrades RNA in RNA:cDNA hybrids, resulting in shorter cDNA fragments (<5 kb) [32]. MMLV reverse transcriptase became a popular alternative due to its monomeric structure, which allowed for simpler cloning and modifications. Although MMLV is less thermostable than AMV reverse transcriptase, it is capable of synthesizing longer cDNA (<7 kb) at a higher efficiency due to its lower RNase H activity [32]. Engineered MMLV reverse transcriptases (e.g., Invitrogen SuperScript IV Reverse Transcriptase) feature even lower RNase H activity (RNaseH–), higher thermostability (up to 55°C), and enhanced processivity, resulting in increased cDNA length and yield, higher sensitivity, improved resistance to inhibitors, and faster reaction times [32].

Table 2: Comparison of Reverse Transcriptase Enzymes

| Attribute | AMV Reverse Transcriptase | MMLV Reverse Transcriptase | Engineered MMLV Reverse Transcriptase |

|---|---|---|---|

| RNase H Activity | High | Medium | Low [32] |

| Reaction Temperature | 42°C | 37°C | 55°C [32] |

| Reaction Time | 60 minutes | 60 minutes | 10 minutes [32] |

| Target Length | ≤5 kb | ≤7 kb | ≤14 kb [32] |

| Relative Yield (with challenging RNA) | Medium | Low | High [32] |

Reaction Components: A complete reverse transcription reaction includes several key components beyond the enzyme and RNA template: buffer (to maintain favorable pH and ionic strength), dNTPs (generally at 0.5–1 mM each, preferably at equimolar concentrations), DTT (a reducing agent for optimal enzyme activity), RNase inhibitor (to prevent RNA degradation by RNases), nuclease-free water, and primers [32].

Primer Selection: The choice of primer depends on the experimental aims:

- Oligo(dT) Primers: Anneal to the polyA tail of mRNA, enriching for protein-coding transcripts.

- Random Hexamers: Prime throughout the transcriptome, providing broader coverage including non-polyadenylated RNAs.

- Gene-Specific Primers: Target particular transcripts of interest, offering high sensitivity for specific targets.

Reaction Conditions: Reverse transcription reactions typically involve three main steps: primer annealing, DNA polymerization, and enzyme deactivation [32]. The temperature and duration of these steps vary by primer choice, target RNA, and reverse transcriptase used. For RNA with high GC content or secondary structures, an optional denaturation step can be performed by heating the RNA-primer mix at 65°C for 5 minutes followed by chilling on ice for 1 minute [32]. If using random hexamers, incubating the reverse transcription reaction at room temperature (~25°C) for 10 minutes helps anneal and extend the primers [32]. DNA polymerization is a critical step where reaction temperature and duration vary depending on the reverse transcriptase used. Using a thermostable reverse transcriptase allows for higher reaction temperatures (e.g., 50°C), which helps denature RNA with secondary structures without impacting enzyme activity, resulting in increased cDNA yield, length, and representation [32].

cDNA Library Preparation for Sequencing

Standard and Advanced Library Preparation Methods

Once cDNA is synthesized, it must be prepared into a sequencing library compatible with high-throughput platforms. The exact procedure varies depending on the platform and specific research requirements, but generally involves fragmenting the cDNA, adding platform-specific adapters, and performing quality control before sequencing [30].

Traditional library preparation methods involve several steps: cDNA fragmentation, end-repair, adapter ligation, and size selection. However, newer, more efficient protocols have been developed. For example, the SHERRY (sequencing hetero RNA-DNA-hybrid) protocol profiles polyadenylated RNAs by direct tagmentation of RNA/DNA hybrids and offers a robust and economical method for gene expression quantification, particularly suitable for low-input samples (e.g., 200 ng of total RNA) [33]. This method streamlines the process by combining tagmentation and library generation steps, reducing hands-on time and potential sample loss.

Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD) Considerations

In certain applications, particularly in clinical diagnostics for rare disorders, it is important to consider the effects of Nonsense-Mediated Decay (NMD), a cellular surveillance mechanism that eliminates transcripts containing premature termination codons [34]. When investigating genetic variants expected to introduce premature stop codons, NMD can mask the underlying molecular event by degrading the mutant transcript before it can be detected.

To address this challenge, researchers can use NMD inhibitors such as cycloheximide (CHX) during cell culture prior to RNA extraction [34]. Treatment with CHX has been shown to successfully inhibit NMD, allowing for the detection of transcripts that would otherwise be degraded [34]. The effectiveness of NMD inhibition can be monitored using internal controls such as the NMD-sensitive SRSF2 transcript, which shows increased expression upon successful NMD inhibition [34].

RNA-Seq Experimental Workflow from Sample to Sequence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-Seq Library Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RNase Inhibitors | Prevents RNA degradation during extraction and processing; critical for maintaining RNA integrity [32]. | Included in reaction buffers or added separately to prevent degradation by environmental RNases. |

| DNase Reagents | Removes contaminating genomic DNA to prevent false positives and background noise [32]. | Traditional DNase I or thermolabile double-strand-specific DNases (e.g., Invitrogen ezDNase Enzyme) [32]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA (90% of total RNA) to enrich for other RNA types [30]. | NEBNext rRNA Depletion Kit, Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit [30]. |

| Reverse Transcriptases | Synthesizes complementary DNA (cDNA) from RNA template [32]. | AMV RT, MMLV RT, or engineered MMLV RT (e.g., SuperScript IV) with improved properties [32]. |

| NMD Inhibitors | Inhibits nonsense-mediated decay to detect transcripts with premature termination codons [34]. | Cycloheximide (CHX) treatment of cells before RNA extraction [34]. |

| Library Prep Kits | Prepares cDNA for high-throughput sequencing through fragmentation, adapter ligation. | Standard Illumina kits or specialized protocols like SHERRY for low-input RNA [33]. |

| Quality Control Assays | Assesses RNA integrity and quantity before library preparation. | RIN analysis, fluorometric quantification, capillary electrophoresis. |

The standard RNA-Seq workflow from RNA isolation to cDNA library preparation represents a sophisticated yet accessible methodology that forms the foundation of modern transcriptomics. By adhering to rigorous quality control measures during RNA extraction, selecting appropriate reverse transcription and library preparation strategies, and understanding the functional roles of key reagents, researchers can generate high-quality cDNA libraries suitable for comprehensive whole transcriptome profiling. This technical foundation enables the investigation of complex biological questions in basic research and drug development, from identifying novel biomarkers to understanding mechanisms of disease pathogenesis. As RNA-Seq technologies continue to evolve, with innovations in low-input methods and streamlined protocols, the core principles outlined in this guide will remain essential for generating robust, reproducible transcriptome data.

Whole transcriptome profiling aims to generate a comprehensive picture of gene expression. However, a significant technical hurdle exists: in total RNA extracts, ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes 70–90% of all RNA content, while messenger RNA (mRNA) represents only a small fraction (approximately 1–5%) [35] [36]. Sequencing total RNA without pre-treatment is therefore highly inefficient, as the majority of sequencing reads and resources are consumed by abundant, often non-target rRNA species.

To overcome this, two primary strategies are employed: mRNA enrichment via poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion. The choice between these methods is a foundational decision that directly impacts data quality, experimental cost, and the biological scope of a whole transcriptome study. This guide provides an in-depth technical comparison to inform this critical choice.

Core Methodologies and Mechanisms

The two strategies operate on fundamentally different principles to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio in RNA-Seq data.

mRNA Enrichment via Poly(A) Selection

This method uses oligo(dT) probes attached to magnetic beads to selectively bind the poly(A) tails of mature, protein-coding mRNAs. After hybridization, non-polyadenylated RNA is washed away, and the purified mRNA is eluted from the beads [36]. This process is highly effective for enriching mature mRNA, which typically makes up only about 5% of total RNA [37].

rRNA Depletion

rRNA depletion uses species-specific probes that are complementary to rRNA sequences. These probes hybridize to the rRNA in a total RNA sample. The probe-rRNA complexes are then removed, typically through magnetic separation (if the probes are biotinylated) or enzymatic digestion (e.g., using RNase H). This leaves behind a diverse pool of RNA, including both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated species [38] [36].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The choice between enrichment and depletion has profound and quantifiable impacts on sequencing efficiency and output. The following table summarizes key performance metrics derived from comparative studies [37].

Table 1: Performance Comparison Between Poly(A) Enrichment and rRNA Depletion

| Feature | Poly(A) Enrichment | rRNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Usable exonic reads (blood) | 71% | 22% |

| Usable exonic reads (colon) | 70% | 46% |

| Extra reads needed for same exonic coverage | — | +220% (blood), +50% (colon) |

| Transcript types captured | Mature, coding mRNAs | Coding + non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs, snoRNAs, pre-mRNA) |

| 3'–5' coverage uniformity | Pronounced 3' bias | More uniform coverage |

| Performance with degraded RNA (FFPE) | Poor; strong 3' bias, low yield | Robust; does not rely on intact poly(A) tails |

| Sequencing cost per usable read | Lower | Higher (requires greater depth) |

Efficiency and Cost Implications

The data in Table 1 highlights a critical trade-off. Poly(A) enrichment is vastly more efficient for sequencing mRNA, yielding a high percentage of exonic reads. One study found that to achieve similar exonic coverage, rRNA depletion required 220% more reads from blood and 50% more from colon tissue compared to poly(A) selection [37]. This directly translates to higher sequencing costs for rRNA depletion when the goal is standard mRNA expression analysis.

Transcriptomic Breadth

While less efficient for mRNA, rRNA depletion provides a much broader view of the transcriptome. It captures both polyadenylated and non-polyadenylated transcripts, including long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), circular RNAs, and pre-mRNA [21] [37]. This makes it indispensable for comprehensive transcriptome annotation and studies focused on non-coding RNA biology.

Experimental Protocols and Optimization

Optimized Protocol for mRNA Enrichment with Oligo(dT) Beads

Following manufacturer protocols for mRNA enrichment can yield suboptimal results, with rRNA sometimes still constituting up to 50% of the output [35]. An optimized protocol for S. cerevisiae, which can be adapted for other eukaryotes, involves:

- Input and Bead Ratio: Use 5-75 μg of high-quality total RNA (RIN > 8). A critical parameter is the beads-to-RNA ratio. Increasing the ratio of Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads to RNA to 50:1 or 125:1 significantly reduces residual rRNA content to about 20% [35].

- Two-Round Enrichment: For maximum purity, a two-round enrichment process is highly effective.

- First Round: Perform an initial enrichment with a standard beads-to-RNA ratio (e.g., 13.3:1).

- Second Round: Use all eluted RNA from the first round as input for a second enrichment with a high beads-to-RNA ratio (e.g., 90:1). This strategy can reduce the rRNA content in the final sample to less than 10% [35].

- Quality Control: Assess enrichment efficiency using capillary electrophoresis (e.g., TapeStation) or Bioanalyzer to quantify the reduction in 18S and 28S rRNA peaks [35].

rRNA Depletion Methodologies and Considerations

rRNA depletion methods can be broadly categorized, with performance differences noted in comparative studies:

- Probe Hybridization & Capture: This method uses biotinylated DNA or LNA probes that hybridize to rRNA. The complexes are removed with streptavidin-coated magnetic beads. Kits employing this method (e.g., riboPOOLs) have shown high efficiency, comparable to the discontinued but highly effective RiboZero kit [38].

- Enzymatic Depletion (RNase H): This method uses DNA probes hybridized to rRNA, followed by digestion of the RNA-DNA hybrids by the RNase H enzyme. While fast and streamlined, studies indicate that this method can cause partial mRNA degradation, leading to 3' bias in subsequent sequencing data, meaning coverage is skewed toward the 3' end of transcripts [39]. It is therefore more suitable for total RNA sequencing applications where full-length transcript integrity is less critical.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for RNA Selection

| Reagent / Kit | Type | Key Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT)25 Magnetic Beads | mRNA Enrichment | Selects polyadenylated RNA via magnetic separation. | Requires optimization of bead-to-RNA ratio; cost-effective for bulk reagents [35]. |